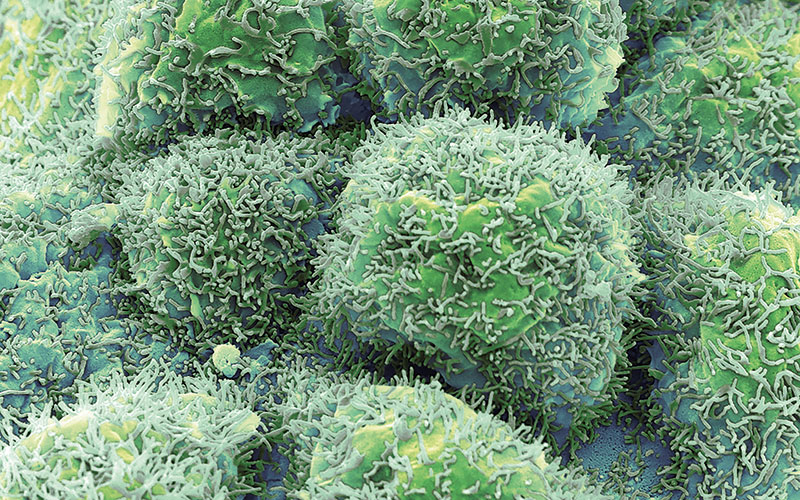

Some of the mechanisms by which polyps develop into colorectal cancer, setting the framework for improved surveillance for the cancer utilising precision medicine, have been revealed.

A new study describes findings from a single-cell transcriptomic and imaging atlas of the two most common colorectal polyps found in humans: conventional adenomas and serrated polyps.

They determined that adenomas arise from expansion of stem cells that are driven by activation of WNT signalling, which contributes to the development of cancer, while serrated polyps derive into cancer through a different process called gastric metaplasia.

The finding about metaplasia, an abnormal change of cells into cells that are non-native to the tissue, was surprising, the researchers said.

“Cellular plasticity through metaplasia is now recognised as a key pathway in cancer initiation, and there were pioneering contributions to this area by investigators here at Vanderbilt,” said Ken Lauone, corresponding author.

“We now have provided evidence of this process and its downstream consequences in one of the largest single-cell transcriptomic studies of human participants from a single centre to date.”

They performed single-cell RNA sequencing, multiplex immunofluorescence and multiplex immunohistochemistry on the samples, which were collected from diverse sex, racial and age groups.

The cells from serrated polyps did not exhibit WNT pathway activation nor a stem cell signature. Moreover, the researchers observed that these cells had highly expressed genes not normally found in the colon, leading them to hypothesise that metaplasia plays a role in how serrated polyps become cancerous.